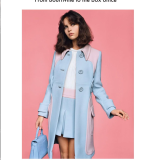

Aston Martin has launched its most significant product marketing campaign of 2022, with its benchmark-setting luxury SUV DBX707 the star of a new cinematic film featuring acclaimed British actor Felicity Jones.

The emotive creative, shot amongst the intense British landscape of Dartmoor National Park, features the BAFTA and Academy Award nominated actor delivering a powerful monologue to camera as an Aston Martin Racing Green DBX707 appears on the horizon and roars into its commanding role.

Renato Bisignani, Global Head of Marketing & Communications at Aston Martin said: “This captivating short film is an example of Aston Martin’s drive to inject emotion and intensity to our product marketing, challenging the creative conventions that customers have become accustomed to from the automotive sector”.

“Eight months on from its breath-taking reveal, DBX707 continues to impress drivers with its thrilling performance, supercar driving dynamics and unmistakable style. Through this content, we have sought to bring those attributes to life in a creative way, pairing a powerful script with an elegant performer who delivers a strong, intense performance. Filmed and produced in the UK, the campaign reflects our passion for partnering with leading British talent to bring Aston Martin’s brand and our unique combination of ultra-luxury and high-performance to life”.

Launched today across Aston Martin’s global social media channels and targetted media placements, the film and accompanying Power.Driven. creative is the first major product marketing campaign launched since the reveal of Aston Martin’s bold new creative identity Intensity.Driven. earlier this year.

Source : media.astonmartin.com